Sermon

Missing Faces, Missing Persons

Speaker: Gene C. Miller

The 15 February 2015 Transfiguration Sunday presentation was adapted from a series of blogposts on my family history blog. The introduction in the blog differs from the Sunday presentation (mainly in that I didn’t tell use the Smith Island Cake story) but the rest of the material, save the ending, is essentially what is found at the links below. The story is sequential and so the links should be read accordingly, followed by—you guessed it—the concluding comments.

Scriptures: Genesis 33:1-10; Matthew 25:35-40; Mark 9:2-10

Chapter 1— “Missing Persons in Garrett County (Part I)”:

Chapter 2—“Missing Persons in Garrett County (Part II)”:

Chapter 3—“Missing Persons in Garrett County (Part III)”:

Chapter 4—“Frostburg: An Apartheid of Memory”:

Concluding comments:

Today is Transfiguration Sunday. Some people seem to think that “transfiguration” means something like what happens to Dr. Bruce Banner when he turns into the Hulk. But that makes no sense to me now. These days, when I think of “transfiguration,” I think of the Old Testament Lesson we heard just a bit ago.

Genesis 33:10: “And Jacob said, Nay, I pray thee, if now I have found grace in thy sight, then receive my present at my hand: for therefore I have seen thy face, as though I had seen the face of God, and thou wast pleased with me.”

When Jacob looked into his brother’s face, he saw God. That had not happened before, and I would suggest that the preceding verses tell us why. The face of his brother, Esau, had long been the face of his sibling rival, and Jacob figured he was going to die at Esau’s hand. But now, after the struggle with the messenger from God that immediately precedes these verses, Jacob sees his brother’s face through his own woundedness rather than through his imagined position of strength. It is only when he looks through his woundedness that he sees God in Esau’s face. Transfiguration which enables him to glimpse Transcendence.

And what is it to live religiously but to live in the awareness of transfiguration and Transcendence? “If ye have done it unto the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me?” is not trying to teach us to pretend to be Jesus by helping others. It’s trying to teach us about transfiguration—glimpsing Transcendence in the faces of the least of these my brethren. The missing faces, the missing persons.

A personal postscript: You might wonder why I’m interested in these issues. The reasons are manifold: let me add to the complexity. To help explain it, I will ask you to pull out the insert that you received with today’s bulletin.

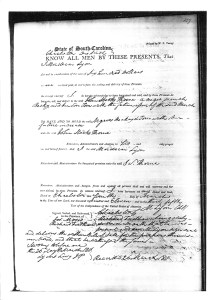

This insert is a copy of a bill of sale. It records the March 4, 1811 sale in Charleston, South Carolina of a “Negro wench Becky and her son Tom with the future increase of said wench.” A man named Mordecai Lyon sold them; a man named John Stocks Thorne purchased them. As noted on the bill of sale, the price Thorne paid for Becky, her son Tom, and her “future increase…” was $600.

We’ve all heard about slavery but not so many of us have seen the actual bills of sale through which persons were treated and transferred as if they were things. Property. I wanted us all to see one.

One of the unusual things that came out of this transaction was that three weeks after John Stocks Thorne purchased Becky and her son Tom from Mordecai Lyon, he manumitted them: he set them both free. It turns out that John Stocks Thorne was in fact the father of Becky’s son, Tom. Becky thereafter became known as Rebecca Thorne and lived with John Stocks Thorne as his common law wife for another sixteen years. They had four more children after Tom. There is no record that John Stocks Thorne had any other wife or children.

When John Stocks Thorne died in 1827, he left money and property in a trust to provide for Rebecca and their children, just as any loving husband would do. We have his will which identifies all his children by name and specifies his wishes that they be provided for.

John Stocks Thorne was a member at St. Michael’s Episcopal at Meeting and Broad Streets in Charleston, South Carolina. When he died, he was buried in the St. Michael’s churchyard. You can visit his grave today. It’s behind the brick wall in the foreground, next to the church.

This is John Stocks Thorne’s headstone in St. Michael’s churchyard. When his common-law wife, Rebecca, died in 1865, she could not be buried here beside her husband because she was the wrong color. Instead, she was buried in the Lutheran Colored Cemetery about a mile north of St. Michael’s. The Lutheran Colored Cemetery where she was buried has been abandoned and is now a vacant lot.

That’s my wife in the picture above. She of course makes any picture look better, but that’s not the only reason she’s in the picture. She’s there because John Stocks Thorne was her great-great-great-great-grandfather and Rebecca Thorne was her great-great-great-great-grandmother.

Twenty years ago, we knew none of this. Missing faces; missing persons. So my interest in these matters is not just history or theology; it’s personal.

You shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you….

The LORD bless you and keep you;

The LORD make his face to shine upon you, and be gracious unto you;

The LORD lift up his countenance upon you, and give you peace.

Amen.